From High School Teacher to UX Strategist

I've been on both sides of EdTech products—and that changes everything

Task-based Design

Developing Workflows

UX Design

Product Design Strategy

Cognitive Load Theory

UX Strategy

Jan 22, 2026

Many EdTech designers have never taught a class. They've observed classrooms, sure. They've interviewed teachers. But they've never stood in front of 30 teenagers trying to explain very cool science stuff while watching their carefully planned lesson fall apart in real time.

I did that for 15 years. And it turns out that experience is exactly what makes me better at designing educational technology.

The Pattern I Couldn't Unsee

Here's what I noticed in my classroom: Every year, students would get stuck designing experiments at the exact same point. They could perform experiments that I designed and handed them. And I knew that they had the ability to think like scientists—all humans start out as mini-scientists. (That toddler throwing the thing off the high chair repeatedly? Scientist!)

But every time I'd ask them to design an experiment, they'd write the purpose and a hypothesis if appropriate. (Contrary to the myth of "The Scientific Method"—not everything is hypothesis-driven and not everything follows the same five steps.)

Then they did one of two things: either sat there staring at a blank piece of paper because they knew "materials" came next but they didn't know what materials they needed, or they wrote down every piece of glassware they knew of...because they didn't know what materials they needed.

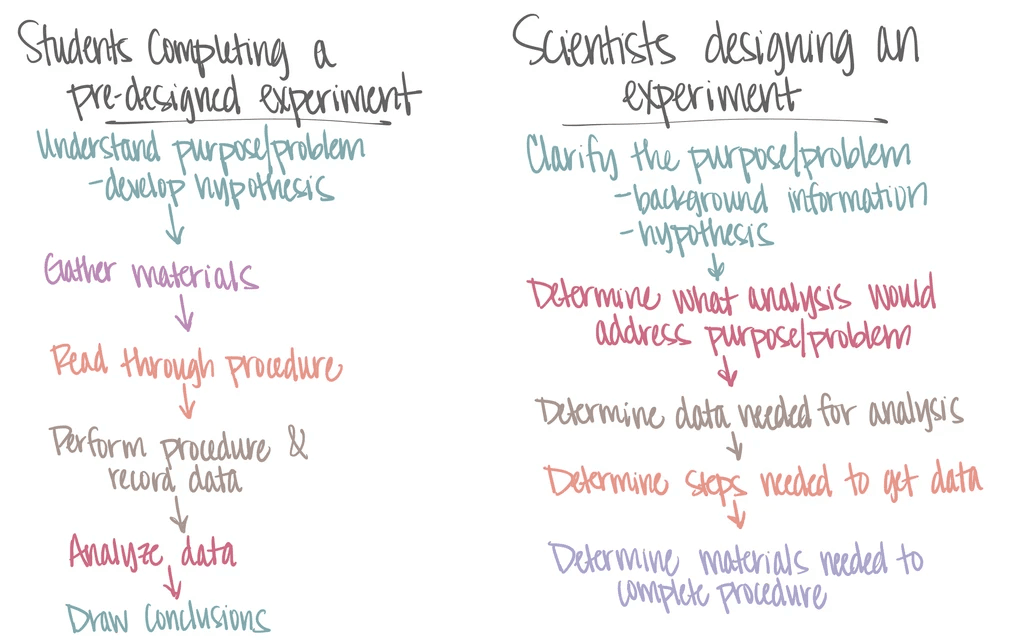

They didn't realize that the way an experiment is written up for someone to read and perform is not the way that it was created. We have to understand what kind of information or data will ultimately help us reach the goal (the results section), then we have to figure out how to get that data (the procedure or methods section), and THEN we can make a list of materials once we know what we'll actually be doing.

And even when I convinced them to design their experiments in this "backwards" way in theory, they didn't actually do it because they didn't think it was OK for their paper to be in this "backwards" order (even thought I told them it was fine to turn it in that way because I not only knew why they did it, but I instructed them to!).

On top of all that, they were trying to design these experiments while learning and applying the science involved, referencing a rubric, and just being teenage humans. That's a lot of cognitive load.

They whined and complained, and after the first time, any time I even mentioned doing another student-designed experiment, they all but revolted. Students thought it was too hard, they couldn't do it, they couldn't design their own chemistry experiments. I knew they were wrong, and I knew it was important that I keep trying to include student-designed experiments in my classroom.

All of this had taken place in the first 7 years of teaching prior to starting my PhD program where I studied the intersection between cognition and learning with UX of instructional technology.

That's when I realized: this wasn't a student problem. This was a design problem.

Building My First "Product"

I spent the next year building a stand-alone application to scaffold the experiment design process as my PhD dissertation. I knew how scientists thought about designing experiments, and I knew the behaviors and thought processes of my students from countless observations. I used task-based design and knowledge profiles before I knew what those were (I wouldn't learn those terms until years later, but understood the principles behind them from my experiences.)

The application broke down the process into manageable steps. It led them through the backwards design process, displaying only the information students needed at each step—both what they'd written in previous steps (but only if it was important to the current one), any specific teacher notes or instructions for the step, and the rubric for that single step. It used progress indicators so students knew where they were in the process and what came next. Then it gave them a finished write-up that was in the "correct" order automatically to turn in.

I was applying cognitive load theory and minimizing split attention effects, as well as closing knowledge gaps between what students knew and what they needed to perform the task.

The results? Student scores increased 18% with a very large effect size (0.82—HUGE in educational research). The peer-reviewed study got published, and I earned my PhD. More importantly, I watched students who had been completely stuck suddenly produce work they didn't know they were capable of.

What Teaching Taught Me About UX

That classroom experience gave me something most UX designers don't have: deep understanding of how learning actually happens under real constraints.

I know to observe workflows, not just interview about them. Students would tell me they understood how to design via the "backwards" process. But watching them try to do it while managing seven other cognitive tasks simultaneously showed me the real problem. This is exactly why I push EdTech teams to do task-based research for both teacher and student tasks—what users say they need and what they actually need during their real workflow are often completely different things.

I know that cognitive load isn't just an academic concept. When you're designing for learning environments, every additional click, every piece of extraneous information, every moment where users have to remember something instead of seeing it directly—all of that competes with their ability to actually learn or teach. Bad UX doesn't just frustrate teachers. It makes education impossible.

I know that the teacher perspective is everything. You can build the most beautiful student interface in the world, but if the teacher setup takes 45 minutes and requires six tutorial videos, your product won't get used. Teachers control adoption. They're already managing 30 different students with 30 different needs. Your product either makes their job easier or it gets abandoned.

The Advantage You Can't Replicate

Here's what 15 years in classrooms gives me that other UX strategists can't easily replicate:

I know what actually happens in schools, not what we imagine happens. I know that "just five minutes of setup" is a dealbreaker when you have four minutes between classes and a printer that jams. I know that September and January are completely different from April in terms of what teachers can handle learning.

I understand the three-user dynamic intuitively. I've been the teacher who had to use poorly designed admin-purchased software. I've been the one adapting a student-facing tool on the fly because the workflow didn't match how my class actually ran. I've lived the tension between what administrators need, what teachers can manage, and what students experience.

I can spot when a design solution works in a demo but will fail in a real classroom with real constraints. Because I've been that teacher trying to troubleshoot technology while managing 30 students, explaining a concept, and watching the clock.

I've also been the teacher practicing malicious compliance—using a product just enough to not get in trouble with my administrators but not enough to generate actual value for me or my students because it doesn't fit our reality and workflows.

Why This Matters for Your EdTech Product

When I work with EdTech companies now, I'm not just bringing UX expertise. I'm bringing the perspective of someone who has lived on the other side of your product decisions.

I know when your "streamlined" teacher setup is actually adding cognitive load. I know when your student interface looks clean but requires too much scrolling during timed activities. I know when your admin dashboard has all the right data but doesn't answer the question principals actually need answered before they'll renew.

Most importantly, I know how to observe what's really happening in user workflows and translate that into strategic design decisions. That's what my academic studies and lived classroom experience taught me. That's what building that first application taught me. And that's what 15 years of watching students struggle and succeed (while I struggled with the demands on teachers) taught me.

You can hire designers who will make your product look good. You can hire researchers who will run studies. But finding someone who has lived the teacher experience, understands the cognitive science behind how learning works, and can translate that into strategic UX leadership? That's a lot harder to replicate.

That's the advantage I bring to every EdTech engagement. And it's why I can help your team see what other designers miss.